“The RA, or somebody in a similar position, has a responsibility to connect a reporting student to a place where they can be made aware of all of their options for getting help, for proceeding to hold their offenders accountable or for getting support,” Hurt said.

Pino said this is problematic for an RA’s work-life balance.

“As RAs, we’re all students first and we have relationships that existed prior to our role,” she said. “If someone tells me something in confidence, and they’re not in immediate danger, and they’re not my resident, do I really have jurisdiction over them?

“They come to me because I’m a (sexual assault) survivor, not because I’m an RA. It doesn’t really make sense at all why RAs have such a huge jurisdiction, when really they’re not qualified to help students who aren’t in their residence halls.”

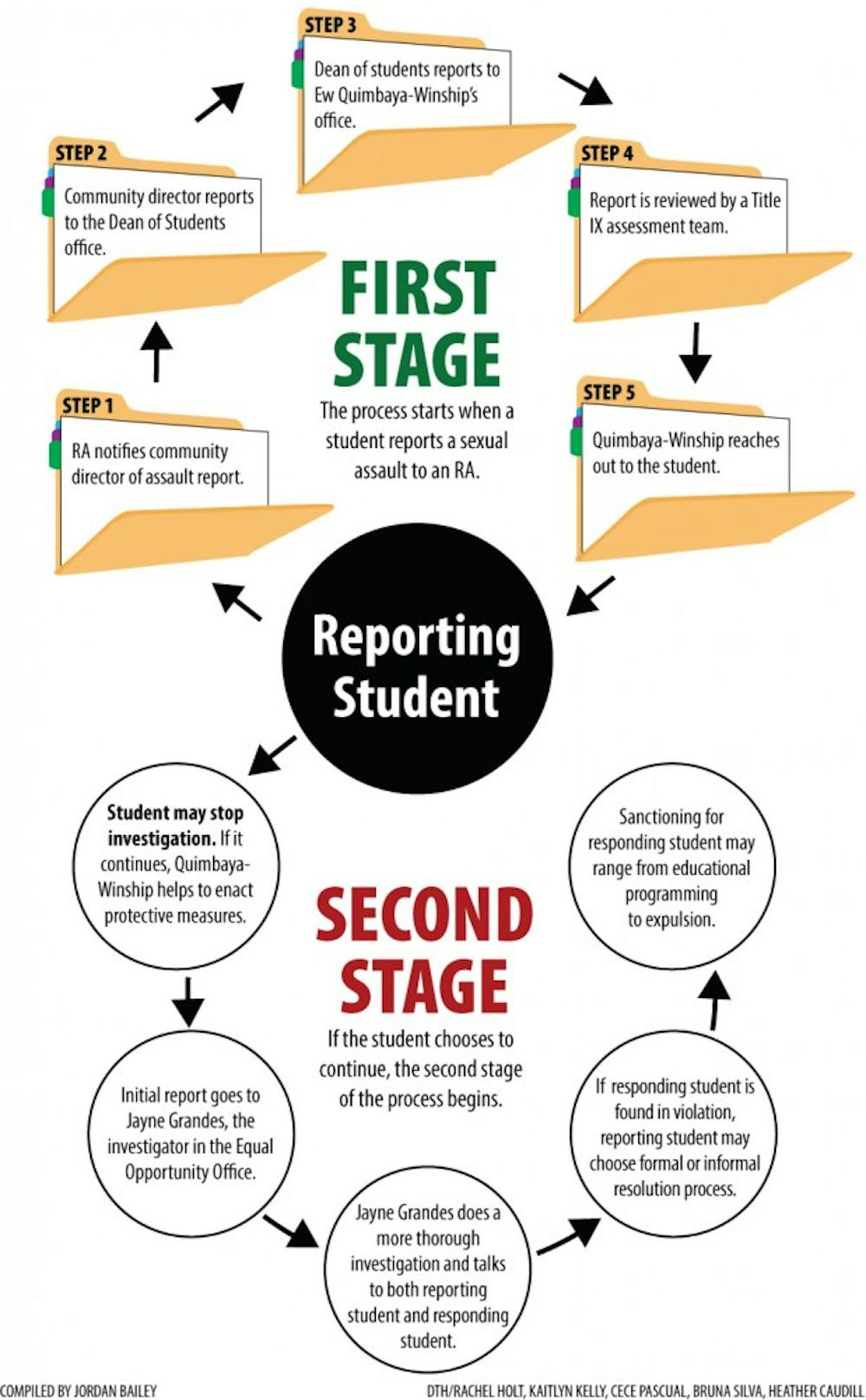

When an RA reports to their community director, the report ultimately reaches Quimbaya-Winship, who will reach out to the victim. The student can then choose to meet with him and move forward with the case, or ignore him altogether.

Savita Sivakumar, an RA in Granville Towers West, said she hasn’t been confronted with any reports of sexual assault yet this year. But she said she feels the rule puts RAs in a difficult spot.

“I think it does put RAs in kind of a hard position because we want our residents to feel totally comfortable talking to us,” Sivakumar said “I think (the rule) makes it a little bit harder for residents to talk to us.”

Sarah Jane Bassett, an RA in Granville East, said she thinks the policy is beneficial.

“I think if a resident came to me with that kind of information, they’d be coming to me looking for help,” Bassett said.

“So I think (the mandatory reporting rule) betters the situation because I’m obligated to report it, so I don’t have to think twice about having to help the student.”

RAs are not the only employees on campus who are affected by the policy. According to the University’s current sexual assault policy, any employee with an administrative or supervisory position must notify the Equal Opportunity/ADA Office of any sexual assault.

“There are expectations that certain units across our campus will report,” Quimbaya-Winship said.

To get the day's news and headlines in your inbox each morning, sign up for our email newsletters.

“Generally speaking, it’s someone that either has the authority to respond to these issues … or someone who students would reasonably consider has the authority or responsibility to respond to these issues.”

Defining the role

The policy, which stems from the federal level, plays out differently at every University.

“There is broad (federal) guidance and schools have to grapple with the interpretation of that guidance,” said Gina Smith, a sexual assault legal expert whom the University hired last year.

“And what we’re seeing nationally is that there is a range. Some schools include all employees as responsible employees, and some designate a smaller set of employees with significant supervisory or administrative responsibility, which may include student employees with significant responsibility for student welfare.”

The University of Montana requires all university employees to report any instances of assault within 24 hours of learning of the incident. Oberlin College considers any member of the campus community a mandatory reporter, Hurt said.

Quimbaya-Winship said the University is still defining who, exactly, is included in the “responsible employee” category. But campus safety employees, SafeWalkers, teaching assistants, department heads and administrators are all considered mandatory reporters.

Currently, no punishment exists for not reporting an instance of sexual assault.

While the broad nature of the policy allows each school to tailor it to its specific needs, Pino said the ambiguity of the policy is problematic.

“As important as it is to connect a student to resources, the policy overall is very overarching and very ambiguous,” she said.

“It’s overstepping and assuming that every assault looks a certain way. It’s assuming that the person wants you to report when they don’t. Most of the time they don’t.”

Senior Grace Peter, an employee at UNC Student Wellness, said her position also makes her a mandatory reporter.

Since taking the job, Peter has had to report one instance of sexual assault. She said a student reached out to her online, and Peter reported it because she felt she had to.

But she said she didn’t feel she handled the situation well.

“This girl thought she was talking to me in confidence,” Peter said.

“(She) was really scared and didn’t know what to do, and I felt like I betrayed her trust even more than it already had been. It freaked her out, and now I don’t think she’s going to do anything reporting-wise.

“At that point I felt like I was being more intrusive than helpful, so I kind of backed off in a position where normally I probably would’ve kept checking in with her and seeing if everything is OK.”

Quimbaya-Winship stressed that there are several confidential spaces in the community where students can go to talk about an assault. These include Counseling and Psychological Services, the University Ombuds office and the Orange County Rape Crisis Center, among others.

“You don’t go there to report, you go there to get support,” he said.

“So I think we’re also trying to clarify that language.”

And even if a student unknowingly confides in a mandatory reporter, they can choose not to pursue any further action against the accused person.

Quimbaya-Winship said the only time he might encourage a student to meet with him or take action is if there is a threat to the broader campus community.

“Let’s say this is the third report this month, and the behaviors described in the report are identical to other assaults that we’ve had on campus,” Quimbaya-Winship said.

“I’m going to want to try to do something about it.”

Training

Quimbaya-Winship said because those who are considered responsible employees’ roles are not clearly defined, not everyone on campus who might be considered a mandatory reporter has received proper training on the subject.

Smith said training on this subject does not need to be extensive.

“It’s a simple message,” Smith said.

“It’s not elaborate training. When you hear something, share it centrally with the trained Title IX professionals, who will sensitively communicate all available resources and options for proceeding.”

But Peter said she feels a more thorough training is essential for making mandatory reporting beneficial for survivors.

She said she thinks mandatory reporters should receive better training on how to talk to victims, and how to explain their role as a responsible employee.

“I don’t think mandatory reporting is necessarily a bad thing,” Peter said.

“But it is bad in that, right now, I just know that I’m a mandatory reporter and I know I have to do it. I think there are certain things about reporting that, if (responsible employees) received training on them, could be more successful.”

Sivakumar said in this summer’s training she learned to refer all instances of sexual assault to the community director.

“I think we address it like most situations that RAs handle,” Sivakumar said.

“If anything ever happens with a resident that’s something more serious than just … (giving) study tips and things like that, we go talk to our bosses about it and make a decision based on that. So in my mind, in training it was presented in the same light.”

university@dailytarheel.com